Small Miracles in the Australian Bush

Simon Christen; SRF (SWISS NATIONAL TV)

On 5th January 2020 a 20-minute documentary featuring our efforts on Kachana was aired in Switzerland: Small miracles in the Australian Bush

The following is a translation to the blog

Author: Simon Christen

Tuesday, 07.01.2020, 00:33 am

(Translation and some hyperlinks provided by Kachana Pastoral Company)

Farmer Chris Henggeler uses the simplest of techniques to restore life in desert-like landscapes. What he has tested in the Australian outback could be applied all over the world, he says.

Chris Henggeler has a Vision. He wants to show the world that humans do not only have the potential to destroy nature. “We can help her to revitalise by activating self-healing processes.”

30 years ago, Henggeler took on "Kachana" nearly an hour’s flight in a light aircraft from the nearest out-back town. There he herds cattle across the landscape. Mundane as that may sound, the results nearly defy belief: in desert-like areas life is returning.

Things are greening up again – Chris Henggeler has been living in this part of the Australian Outback for over 30 years. SRF

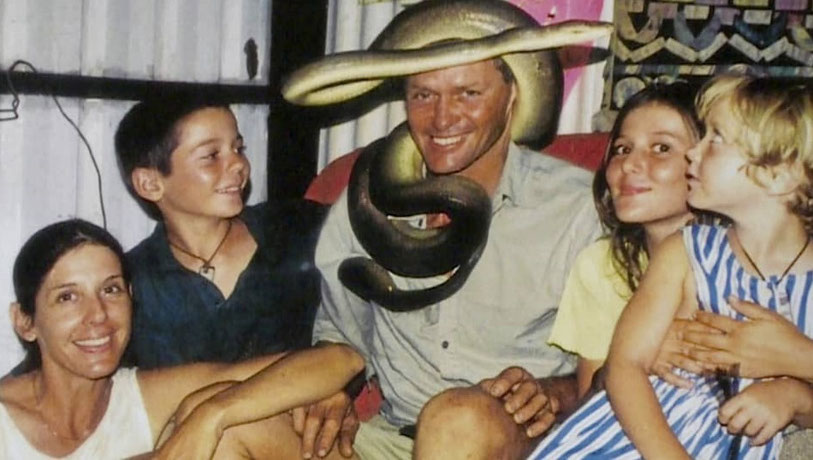

Henggeler was raised on a farm in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). Due to the escalation of the civil war in the early seventies, the Henggeler family returned to Switzerland, where Chris met his bride-to-be. Jacqueline was the daughter of a hotelier in Engelberg. Chris emigrated to Australia, and Jacqueline followed. They started a family and were blessed with three children.

The Henggeler family in the Outback. PRIVATE

A farm in the out-back as a work of love

Chris Henggeler wanted to farm and to understand nature. He took his loved ones to a place that sometimes experienced torrential downpours as well as temperatures above 40 degrees C in the shade. While single he had invested in real-estate which provided income for the family. Work on Kachana was a labour of love with no direct pressure to provide immediate financial returns.

Livestock as gardeners in the landscape

Using a planned management process Henggeler herds cattle through the landscape. The animals are not managed to produce milk or meat. Their job is to be “landscape gardeners”.

The closest physician is an hour’s flight from here. SRF

As they move through the landscape they mulch, fertilise and prune vegetation. Hooves also loosen the surface and allow seeds to find good growing conditions.

The result: the soil comes alive. Rain and sunshine then drive regeneration. Soils are rehydrated, come alive and can again store water.

Re-greening

Henggeler’s results impress: after a few years of targeted land-management perennial creek-flow is restored. There are all sorts of animals and crawly things. Greening wherever you look. In a nutshell: small miracles are occurring in the Australian bush.

Livestock loosen the soil-surface enabling new green. SRF

Now that everybody is talking about climate-change and land-care, Henggeler’s in-the-field research could offer a way forward. The principles he has familiarised himself with apply globally: rebuilding biodiversity, improving water-security, achieving healthier and more productive landscapes. At the same time these landscapes begin to sequester tons of carbon dioxide.

"Mother Nature is our teacher"

Quote: Christoff Henggeler - Farmer

“Through observation we learn where and how to intervene in the landscape in order to initiate and speed up self-healing processes” explains Henggeler. “Our teacher therefore is Mother Nature.”

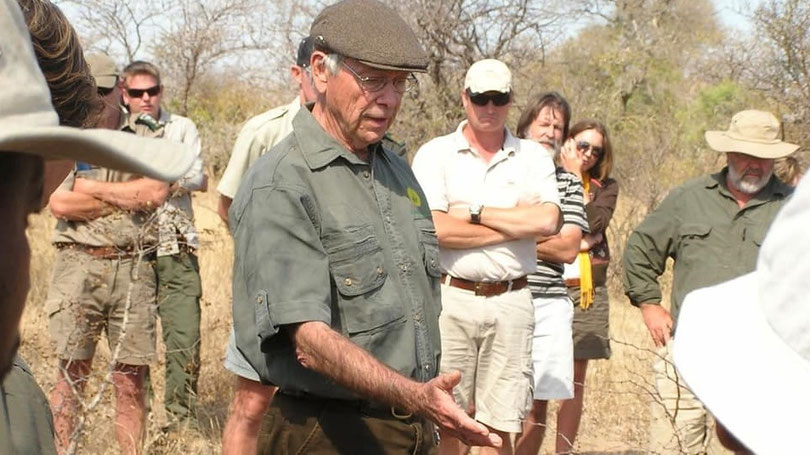

All the while he studied what others had already discovered and applies what is relevant to his particular context. As the leading figure he cites Allan Savory.

Savory, a Zimbabwean ecologist and farmer is a founding member of the “Savory Institute”. He is the father of “Holistic Management”, an adaptive systems-based process to manage land and other complex resources.

Allan Savory

Land-manager and ecologist

Allan Savory is a charismatic as well as controversial figure who has inspired three generations of land-managers all over the world with the holistic principles that he promotes.

Differing approaches to utilising land have evolved that have a common thread: they want to be sustainable and ecologically sound. In Switzerland for example, adherents to what is termed, “Permaculture” refer to Savory.

“Permaculture” is derived from the words “permanent” and “agriculture”, and implies “sustainable agriculture”. Permaculture however strives to go way beyond cropping. The movement sees its role in ecological landscape design. Permaculture principles relate not only to the land, but also to new forms of community-building.

Henggeler is convinced about the enormous potential that his methods can unlock. On the one hand tropical and subtropical regions of Australia could reap great benefit, on the other hand the same applies to desertified regions in the Mediterranean region and parts of Africa.

“Nature does not need us, but we need nature” Henggeler reminds us. Water-security, biodiversity and agricultural potential have become critically limiting factors in many communities on the planet.

Allan Savory has inspired land-managers all over the world. SAVORY GLOBAL

Stepping into CO2-Trading

In other words: his methods could help alleviate the needs for Climate-Migration. And for people in poorer regions of the world new business models could evolve: they could revitalise landscapes and participate in carbon-trading. “Pay us so that we can pull your “rubbish” out of the air” Henggeler suggests.

Henggeler begins the new year with optimism. “People are slowly beginning to wake up”, he sums up his impressions of 2019.

He used to be laughed off as being mad

Environmental custodianship is a topic that current climate-debates have brought to broader public attention. 30 years ago, when Henggeler began studying natural processes, things were different. Back then people chuckled and thought he was mad. Now he gets invited to present. “The scepticism is waning, but action on the ground is nowhere near fast enough.”

The question most often asked is: “Where is the money?”

Great short-term financial benefit can be reaped by mining natural resources. Fortunately, more and more people, especially young people, are becoming aware of the longer-term costs of such behaviour.

“Key is the well-informed consumer who supports ecologically sound regenerative practices.” There are many out there who would rather contribute to solutions than to continue supporting the problem. He therefore remains basically optimistic. “I am father and grand-father, I have to hope…”

A PERSONAL COMMENT FROM CHRIS:

It is a challenge to pack 30+ years into 20 minutes! We thank Simon Christen and the SRF-Team for broadcasting the message of Kachana to an international audience.

Please remember that without the support of the Waser family and many other helpers, donors and supporters over the years, we would not have survived the learning-curve.

Jacqueline and I enjoyed the video and feedback has been diverse and encouraging.

For those interested in more detail, below are answers to other questions that Simon raised in his discussions with us. (At the end of the page we also supply a list of links.)

Questions

1) What are your most important insights after recent decades spent on Kachana?

- It is not “cool” to swim against the current. (It was my good fortune that [when I was about 9 years old] my father convinced me of the need to be able to do so.)

- No matter where we live, each of us modern humans contributes to the processes that are turning this planet into a desert (often this happens in ignorance). - In places, this trend may already have begun thousands (!) of years ago, but it has only started to spiral out of control in the last 70 years or so, with the exponential increase in both human populations as well as in their growing “demand for stuff”.

- Collective human behaviour is now hindering and, in some cases, even preventing critical life-enhancing processes from functioning; as individuals we participate in this process by “not doing anything about it” or “business as usual”.

- Processes contributing to desertification often (but not only!) take place in regions where people do not live or work. (“out of sight, out of mind” remote or abandoned landscapes)

- It is as if our planet is suffering from an anti-immune disorder: What should be life-enhancing forces (sunshine, wind, rain, the behaviour of humans and large animals), now contribute in a destructive manner at landscape levels: dehydration of soils, erosion, dysfunctional behaviour of many remaining large animals.

- Observation often lets us discover where and how we can initiate and enhance self-healing processes.

- Solution: rebuilding biodiversity via biomimicry

- Key: Informed consumers that support regenerative activity.

2) Many might think: What do I care about Henggeler’s discoveries in the Australian out-back…? In what ways might insights gained on Kachana be relevant to ‘the rest of the world’?

- “Henggeler” has not discovered much on his own. Mother Nature has been the teacher and my activities have merely supported findings that were being investigated by people like my Dad and Allan Savory back in the sixties. Only back then the symptoms we see today were not as obvious, and ‘solutions’ lacked rigorous testing. (Solutions applied at the time were already attracting controversy!)

- A world without sufficient fresh water (in the soils, and in the rivers) would be a very dangerous place to live in. (Effective timely action could prevent this from happening.)

- The challenge is to make use of holistically planned Animal-Impact (of herding herbivores) to revitalise soils. (Animals behaving in functional herds, performing the environmental services that their wild ancestors did naturally when predator-prey relationships were still intact.).This is already happening today, but mainly in situations that are financially rewarding. The “reward” that we on Kachana currently aim for, society does not yet seem to place a value on: securing reliable perennial creek-flow. For this to happen we need to build healthy productive soils and biodiversity.

- Healthy microclimates are well populated and alive! Biology does the work that is required to build and to keep them healthy and resilient. Such a healthy microclimate is therefore scale-neutral. It can be grown out to encompass ‘local climate’, ‘regional climate’ and eventually continental climate. It is in this way that we can have beneficial influence on global climate. (Headlines are now being made by symptoms occurring from the reversal of this desirable trend.)

- African climate is already influencing happenings in Europe: weather-related, but also in social domains. Natural disasters and refugee-issues come to mind.

- Practices field-tested on Kachana over the last 30 years can easily be put to use in other arid landscapes. We find situations in France and in Spain where this thinking is already being put to practice.

3) How big is the potential in your estimation? What is achievable? Where? Where not?

-

How big is the potential in your estimation?

That I cannot tell you, but I see it to be enormous. For example, tropical and sub-tropical regions of Australia could easily support four times the current numbers of wild-life and stock (therefore also an equivalent increase in biodiversity!). For deteriorating landscapes in the Mediterranean region, the potential is similar. What we experienced on Kachana is that a multiple of nothing, remains nothing. First, we need to offer biological “micro-credit”. Only when this happens in a targeted and in an effective manner, can we generate the necessary “compounding interest” within our ecology.

-

What is achievable?

The revitalising of soils through healthy vegetation that provides energy for organisms in the soils. This needs to take place beyond farming areas in broader landscape settings. Water-infiltration and a replenishing of groundwater and aquifers is thus facilitated.

-

Where?

It would be best to first ask locals where they experience problems.

One would begin working in watersheds and sub-catchments of drainage-systems; in places with low water-tables, then in places that are threatened by floods and landslides, and in areas that are repeatedly threatened by wildfire.

-

Where not?

Everywhere, where locals do not wish to commit.

4) “Work in the field” does not only take place on Kachana, but in different locations on the planet. Where, in your opinion, do we find interesting results?

Practitioners are mainly active in landscapes where people already live and work, and where the nature of the challenges has been recognised:

And: Is communication taking place between you?

Yes.

5) Has there been a change in public perception?

I’d say, yes, there has been. Especially in 2019!

The general public seems to be waking up. We shall find out if politicians will respond in time.

Are we finding greater interest and more openness to these kinds of approaches?

Scepticism is in decline, but we are not acting swiftly enough; especially so in areas where the human is missing – in areas where our only option is to use the renewable energy that our large animals have to offer.

6) Methods that you and others have been successfully working with have not yet been universally accepted. Why is this the case?

- Ignorance, distraction and greed

- Wilful blindness, that “protects” us from assuming individual responsibility

- Where there is misery/poverty, there often is a lack of funding or knowledge, often combined with a lack of will for self-help.

- Where funds and knowledge would be accessible, there appears to be a general lack of interest. We still have it too easy to consider studying such issues at a deeper level.

- Humans remain after all herd-animals: most would rather fail conventionally than take the “risk” of succeeding unconventionally.

What sort of resistance do you come up against? Too expensive? Too complicated? …?

- Where is the money?

That costs too much!

(Now after 30 years, current band-aid measures alone, are already costing the public purse far more than it would have cost to avoid many of today’s “natural disasters” altogether. – Sure, back then we knew less and our solutions may have been less efficient, but the opportunity costs of “doing nothing” are now weighing heavily upon us.) - That is intensive (management)!

Correct, intensive care is “intensive”. But after all, it is about reviving “patients” and then getting them back to work.) - Is such action sustainable?

(No. It does not have to be; we are temporarily bridging a gap in order to take us to where we can become and remain sustainable!)

And: How can that be changed?

- Support a local regenerative farmer; join her/him on the learning-curve

- Develop your ecological understanding

- Recognise the global connectedness that our actions influence

- Offer support to practical projects and case-studies

- Be wary of supporting band-aid measures

- Education and communication

7) Looking ahead: What will things be like in 50 years?

- Very different. We are so globally connected, that change can take place at exponential rates; either for the better or in a continued downward spiral.

- In general, future generations will live more modest life-styles.

- The collapse of the Roman empire (this is the only comparable situation I am aware of) coincided with the permeation of Christian values. (Then again ecological challenges at the time did not have visible global ramifications. Nonetheless, traces of the impact of mining the ecology back then remain visible even today.) We may soon find out if we remain capable of reviving and reinventing values identified and successfully put to use by our ancestors (whilst making possible the opportunities that so many of us took for granted last century), or whether communities will end up meandering aimlessly within a spectrum ranging from bestial opportunism to the rigid mindlessness of central planning and artificial intelligence.

Do you have much hope?

- I am father and grandfather, I must hope.

- I see, I understand, and I am in command of knowledge that can demonstrably deliver viable outcomes. This allows me to hope.

- There are many good, young people that deserve support. They give me hope.

- There are many (albeit not a high percentage) of people who are wealthy enough to become a significant part of the solution instead of remaining part of the problem. I hope...

- Existing scientifically verifiable insights regarding the relationships between soil-biology and climate, suffice to initiate climate-action in a manner that would have positive ramifications globally. Everybody is still allowed to have hope.

- BUT we need to act swiftly, collectively, and in a coordinated manner!

Or are you rather on the sceptical side?

- "The only thing we can do is rebuild the Earth’s soil carbon sponge and those in-soil reservoirs. That’s a win-win-win. If we don’t do that, it’s lose-lose-dead." Walter Jehne

- My limited knowledge of history as well as personal experiences in past decades lead me to be sceptical.

- By nature, however I remain an optimist!

- As a Christian, l remain positive and remember what my Grandmother told me: “God provides us with nuts, but he does not crack them open for us.”

We thank all those individuals who have assisted us in spreading the regenerative message!

With the disastrous burning of biomass in Brazil and then in Australia late 2019, we see this message to be as relevant as ever.

Below are a few of the links that have helped put Kachana before the public eye in more recent years:

2020

Swiss TV: SRF-Die ganze Geschichte online 2020.01.05 Simon Christen

Swiss TV: SRF-Youtube Simon Christen

"The New Water Alchemists", by Judith D. Schwartz. This story, which was originally published through The Craftsmanship Initiative in 2017, looks at some of the innovative ways that scarce water resources are being managed around the world, and how this basic element can become a powerful tool in our efforts to slow, and even reverse, climate change.

2019

Central Station posted five blogs on Kachana, November 2019.

- Reinventing Landscape-Management through Regenerative Pastoral Practices - Chris Henggeler

- Dreamtime – feeling safe when you sleep helps - Jacqueline Henggeler

- Kachana sterek - Fettes Falconer

- Pastoralists to the rescue - Part 1. New Millennium, New Challenges - Chris Henggeler

- Pastoralists to the rescue – Part 2. When Alarm Bells Ring - Chris Henggeler

2018

- ABC News: Wild donkeys in Kimberley scientific trial in the sights of aerial shooters; 23rd May 2018

- Local Newspaper: Kachana Pastoral Company advertisement in the Kimberley Echo; May 24th 2018

- Youtube: Louise Edmonds does the maths on Kachana Carbon; July 2018

- The RegenNarration: The New Megafauna - Key to future prosperity - with Chris Henggeler; August 2018

- The RegenNarration: Creating the Kachana vision with Jacqueline Henggeler; August 2018

- The RegenNarration: Kachana back-story with Chris Henggeler at the homestead; August 2018

Central Station posted five blogs on Kachana, October 2018.

- Kachana: A 750mm-rainfall desert - Chris Henggeler

- Kachana: What are you doing here? - Jacqueline Henggeler

- Kachana's driveway in the sky - Bob Henggeler

- Can it fly? - Bob Henggeler

- We did not need wings to escape - Kieran Mooney

16th October 2018, at the bidding of the Minister, Chris was invited to present to members of the Ministerial Advisory Committee at the DPIRD Headquarters in Perth: