wild donkey project

why have wild donkeys been allowed to survive on kachana?

Chris Henggeler, Kachana Pastoral Company, November 2017

“ Feral donkeys are declared pests of agriculture in WA under the Biosecurity and Agriculture Management Act, 2007 and programs are in place to control them in the wild. The primary means of control is by shooting from helicopters.”

Read more: https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/pest mammals/feral donkey

Why have wild donkeys been allowed to survive on Kachana?

Justifiably this and other questions come up every time there is a changing of the guard, at local or regional levels. 2017 was such a year.

Prior to addressing this year’s specific questions, allow me to add some context.

1. We are talking about upper catchment country that is not (never was) suitable for conventional pastoral pursuits.

(This reasoning may therefore not apply to the average pastoral lease that is reasonably stocked and managed.)

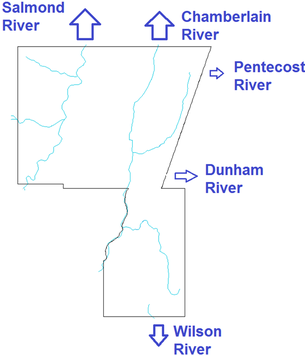

Kachana sheds water to the Wilson, Dunham, Pentecost, Chamberlain and Salmond Rivers

This is the challenge that we inherited - Dry Season 1992

This is where we are now - Dry Season 2015

The change was brought about by strategically managing more mouths and more hoofs each year.

(We are aware that it is early days yet…)

Nature works/responds on her own terms in her own time. The learning continues and we remain on the lookout for better ways.

2. In such country (i.e. country where the bulk is not being managed for pastoral industry purposes) it is safe to say that since the mid-nineties wildfire is now responsible for more ecological damage than the donkeys ever did. (My observations only go back to 1985. Actual monitoring sites have only been in place since1992.)

With the benefit of hindsight, we now argue that it is the behaviour of the animals that is critical and not the species per se, and not their actual numbers.

Please refer to Appendix 1. below for more about how/why we make use of donkeys.

3. Hindsight further suggests that in such areas, donkey eradication (at the speed with which it occurred at the time) was/is a major contributing factor to the fire damage of recent years.

With rapidly reduced grazing pressure (in the absence of some form of hands-on management like "Eco Fire"), smaller local herbivore numbers could not expand fast enough to replace the bulk carbon cycling formerly performed by the donkeys.

As a result, the annual build-up of senescent vegetation set the stage for extensive wildfires with escalating loss of biodiversity across the board (soil organisms, plants, birds and animals).

Local marsupial populations have crashed except for in our model areas.

Those who have read Flannery’s book "Future Eaters", would appreciate that we inadvertently created our own local version of “fire anarchy” similar to what took place on nearly a continental scale after the demise of our original mega fauna after the arrival of the first humans.

4. AWC with its "Eco Fire" approach, I believe is aiming to address this situation. (Remember, it is early days yet.)

5. It too is early days for us here on Kachana.

In our model areas we use primarily the targeted use of herd action. (These concepts explained on YouTube 25 Minutes)

Our results to date are promising. See the attached soil sampling summary in Appendix 2 below.

We feel that this is a fair indication of what is achievable in riparian zones, and with the rebuilding of sponges.

Beyond our model areas we use primarily wild cattle and donkeys to manage fuel loads and to keep fire breaks clean. These “severe grazers” make it easier for the “nibblers” (marsupials) to follow up with keeping fuel-loads in check and any growing vegetation young and fresh.

6. With the decision made about 3000 km to the South of us, a Western Australian Land Act (L.A.1997), put us on the wrong side of the politically correct fence.

This is not the place to go into details. Suffice to say that, by that time we already had too much invested to cut our losses. We needed to keep going.

7. On Landline in 2001 Paul Novelly notably claimed that “the jury was still out”. (“To Burn or Not to Burn”)

This seems to have changed in recent years.

As the cutting edge of science progresses the wisdom of eradication of species is being challenged:

In his recent publication "Call of the Reed Warbler", Charles Massy describes how “new thinking” is beginning to leave its mark on Australian landscapes.

8. The logic of our reasoning (and what they saw happening on the ground) resonated with the donkey shooters at the time. So much so, that with their support we embarked on an experiment whilst awaiting approval/support from higher up the departmental food chain.

(No official interest has been shown to date.)

The agreement on the ground was upheld over the years. Communication at this level has been good and helpful.

9. Meanwhile up-to-date soil science, ecological information and animal behaviour knowledge have come to our assistance. We no longer need to argue the finer points; there are more eloquent PhD wielding people out there now doing that for us.

My suggestion: We focus on what it is that we wish to achieve for our region and for our heirs.

(Let us not get bogged down in departmental politics and with outdated legislation that will take years to be matched to the stream of new scientific information that is coming from the ecological front line.)

Our options:

1. Cull the donkeys and thus terminate the Kachana donkey experiment.

2. Leave things as they are.

3. Explore new win win options.

now to the most recent questions put to us:

What donkey-numbers are on Kachana?

Perhaps a little more than 100 head (barely enough for genetic viability.)

We are more interested in what they do, than in how many there actually are.

From a pastoral/ecological perspective we have nowhere near the numbers we would need to cycle and keep healthy the vegetation in the ranges.

It is safe to say that the wild fire history of the last 25 to 30 years supports this claim.

(Our repeated offer to welcome scientific evaluation still stands.)

Populations seem to have plateaued out, due to predation and a male biased population. If of interest, this would need to be further explored.

How is the population density managed/reduced?

Predation by dingos and the strategic culling of jacks.

Sporadic introduction of a cattle herd into the area to discourage territorial behaviour.

Low stress stockhandling techniques as per Appendix 1. below.

How are donkeys prevented from migrating off Kachana onto other “eradicated” properties?

Low cattle densities for most of the time with better quality feed tends to keep them in the area.

Culling beyond the designated area.

Monitoring via collared animals.

Feedback from shooters in the past indicates that this seems to be working.

We hope the above serves to clarify some thoughts/reservations people might have about our capitalising on “pest species” for land care purposes.

An international team of scientists are studying the place of wild donkeys within Australia’s unique and thriving ecosystems. Ecologists are studying how wild donkeys promote biodiversity and important ecosystem services such as water retention, soil enrichment, and fire suppression; and how donkeys interact with other large mammals in the region, such as dingoes and large marsupials. The research project is looking at alternative models of land regeneration and human-wildlife coexistence within a multi-species justice framework.

A HUGE THANK YOU! to all those wonderful and practical individuals who on our behalf have risked bureaucratic wrath from above, whilst assisting us in the search for locally relevant solutions and options.

A special THANK YOU! To Mark, Amy and Mike who on behalf of the Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue filmed Without a Voice - A documentary film about the plight of Kimberley donkeys which aired May 2020.